You’re So Vain, You Probably Think This Post Is About You

It doesn’t help people to assume they want the same things you do

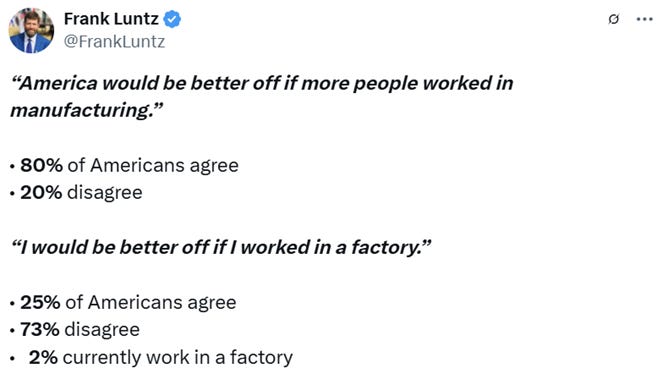

There is an important lesson to be learned about American politics from this tweet by pollster Frank Luntz yesterday that received millions of views:

In a second tweet, Luntz described these findings as “a Rorschach test for people on both sides of the free trade debate. It either shows that pro-manufacturing people (80%) don't actually want to work in factory jobs (25%) or there is potential/willingness (25%) for 10x growth in current factory jobs (2%).”

That’s not the Rorschach test. Both of his statements are of course true, as descriptions of the data. But only the second one is interesting. We’ll come back to why in a bit. But let’s start by zooming in on that first statement: "80% of people agree that “America would be better off it more people worked in manufacturing,” while only 25% agree “I would be better off if I worked in a factory.”

Is that surprising? What should we make of it? The Rorschach test here is one separating people who can think rationally and empathetically about the wide range of opportunities their fellow citizens might pursue, and those who lack that basic capacity. See, if fully 25% of poll respondents say they’d prefer a factory job to their current job, that suggests massive potential unmet by the current labor market. Under those circumstances, 100% of Americans should believe we would be better off if more people worked in manufacturing. Because there are lots and lots of people who are telling pollsters that they want to do that, and probably could. If there’s something amusing in the responses, it is the 20% of people who don’t think his would be good for America, perhaps because they are unaware that the preferences of so many Americans diverge from their own.

Shockingly, yet not shockingly at all, the sorts of commentators proudest of what they consider their clear-sighted ability to see beyond the provincial nostalgia of reindustrialization rushed to dunk the ball accidentally in their own hoop. A smattering of their comments on the Luntz tweet:

Matthew Zeitlin, HeatMap: “Everyone else’s kids should considering [sic] not going to college and working in a factory while my kid goes to college and gets a highly paid service sector job.”

Scott Lincicome, Cato Institute: “Your periodic reminder that the right has its own version of ‘it's for your own good whether you like it or not (mainly not)’ policy.”

George Conway, The Bulwark: “Factories for thee, but not for me.”

Ernie Tedeschi, chief economist at Biden Council of Economic Advisers: “Sums it up.”

Eric Boehm, Reason: “Factories for thee but ‘oh fuck no that sounds miserable’ for me.”

Kyle Smith, Wall Street Journal: “LOLLOL.”

It’s worth teasing out what the logic on this other side of the argument might imply. Presumably, in this view, you should only respond yes to a question about whether America would be better off with more of some job type if you would yourself want to work in that job. We should thus only see majority political support for more jobs of types that most people say they would choose over their current job. Obviously, this makes zero sense. Frankly, I doubt a Lincicome or a Tedeschi would actually try to defend their logic here, if they took the time to consider it.

We see this same kind of thinking elsewhere in our politics. Zeitlin draws one analogy directly, to the idea that there’s something wrong with people who want their own kid to go to college but don’t think we should have an education system oriented toward college for all. “I want my kid to go to college, therefore I must say all kids should go to college” has a sort of comforting moral insularity to it—no one can call me a hypocrite or an elitist now!—even though, in practice, the result is a worse system precisely for the people for whom the non-hypocrite is professing concern.

Another good example is the disconnect between the share of people who are concerned about worsening economic conditions for themselves and the (typically higher) share who are concerned about worsening conditions generally. Often, such results are criticized as reflecting some cognitive bias amongst respondents, who assume things are worse elsewhere than for themselves. But more practically, it represents a recognition that one’s own condition is not determinative of conditions broadly, and if some substantial share of the population is struggling, that is a problem regardless. Again, “well let me check my bank account, I guess things are going well in America” is not the thoughtful perspective.

This style of virtue-signaling from the elite is so obviously self-interested and socially harmful that it’s hard to believe it passes as virtuous at all. Really, we’re going to elevate the assumption that everyone is the same as you and you can best serve others by promoting only those things you want for yourself? The decadence astounds.

What about the actually useful point, that 25% of Americans wish they could get a job in a factor? Somehow, this too is managing to get cast in a negative light.

Luntz found the figure, originally from last summer’s Cato Institute survey, in a Sunday morning Financial Times column by Tej Parikh. Cato’s director of polling, Emily Elkins, presented 25% as a low number, writing that “while 80% believe the country would be better off if more Americans worked in factories, only 25% would themselves like to work in a factory.” Parikh likewise sees it as an obstacle to the reindustrialization project, because it indicates “few Americans want to go into industrial work.”

He gets this doubly wrong, misunderstanding both the project and the figure. The Trump administration’s ambition, he wrote, is to “bring back labor-intensive factory jobs,” quoting Commerce Secretary Howard Lutnick’s recent comment that, “the army of millions and millions of human beings screwing in little, little screws to make iPhones, that kind of thing is going to come to America.” But that gets Lutnick exactly backward.

Immediately after Parikh cuts off the quotation, the commerce secretary continued: “It's going to be automated and great Americans—the tradecraft of America, is going to fix them, is going to work on them. They're going to be mechanics. There's going to be HVAC specialists. There's going to be electricians.” Lutnick is making an important point here, which is that reshoring labor-intensive manufacturing from abroad does not mean doing it in a labor-intensive way here; the jobs in the United States would be much better and more productive ones requiring more skills in more capital-intensive and automated factories.

That’s good! As I noted last year, “the question is not how many people an advanced American manufacturing plant employs as compared to an old-fashioned one with the same level of output. The question is how much it employs compared to one located in China.”

Regardless of what kind of manufacturing Lutnick might envision, Parikh is also entirely wrong to take the fact that “only one in four believe they would be better off in a factory over their current employment” as a problem for reshoring manufacturing.

One in four?! That would be 40 million of 160 million employed Americans! The United States has never had even 20 million people working in the manufacturing sector. When we talk about reindustrializing America, we are talking about adding millions of manufacturing jobs, not tens of millions—several percentage points of the labor force, not a quarter or more. China doesn’t even have close to 25% of its workforce in manufacturing.

So why does manufacturing matter, if we’re only talking about a few percentage points of the workforce rather than, say, the majority? As I explained to Fareed Zakaria on CNN yesterday:

It’s not just about the jobs in the factories. If we had highly productive jobs in factories, didn’t have as many people working in the factories, but they were anchoring local economies, they were anchoring supply chains, they were providing better jobs in those towns in services, I think that would be a terrific outcome. That’s exactly the outcome we should be looking for.

In fact, when the Cato Institute, a very libertarian organization, made a short film about free trade showing how it could work, they showed a community devastated by NAFTA, and then do you know how it came back? Because a new manufacturing plant came into town. Not because everyone was working in the plant, but as they showed because even the pizza place in town is better when the factory is back.

It would be interesting to know a lot more about those 25% of workers who would prefer to work in a factory. What are they doing now? Where are they located? Are there other jobs they would also prefer? But please, let’s stop with the “nobody wants to work in a factory,” and even more so the “I don’t see you working in factory.”

A healthy economy is pluralistic, offering many different paths to a decent life available to people who have just as many different aptitudes and aspirations. A health society is pluralistic too, granting dignity and respect to people regardless of the path they choose. And a healthy politics is pluralistic most of all, celebrating pluralism and embracing an obligation to advance it. An elite that thinks it is supposed to promote only its own path is helping only itself.

- Oren

If it pays well and eliminates the need for people to work 2-3 jobs, people will work in them. If it pays bottom barrel wages then they won't. The logistics industry has been decimated since the 90's. Wages have been stagnant for 15 years or more. Most who work in warehouses need social services to survive, despite working manual labor for 50+ hours a week. It is despicable and not what we were promised about working hard and doing things right. If we don't bring it in and ship it out, no one gets any consumer good. But most of the wages are minimum no matter how hard you work. No meritocracy In the logistic/distribution industry. So the next republican who says that everyone is sitting on their ass and no one wants to work anymore, send them to a warehouse in furniture retail for a week. That message will change real quick.....

Frank Luntz, whom I know, should know better than to throw out almost meaningless survey data without the nuance of crosstabulations. Where's the survey? Remember that 20 percent of Americans are over 65 and likely retired. A third of Americans have college degrees and aren't interested in factory jobs. And where's the information comparing pay between, say, teachers and plumbers or factory workers (guess which one pays better starting salaries?). Luntz disserves.