What’s the Difference Between Economics and Astrology?

At least horoscope writers don’t take themselves so seriously…

A frequent theme here at Understanding America is the problem of economists and economic commentators misappropriating useful economic insights to advance their preferred political projects. With the presidential campaign heating up, Bad Economics is reaching a fevered pitch, in both the often incoherent proposals emerging on the trail and the politicking posturing as analysis from the experts.

A few recent favorites:

THE TRUTH-IN-LABELING PROBLEM

One bad habit is the colloquial misapplication of terms that have technical meanings in economics. Greg Ip, the usually excellent chief economics commentator for the Wall Street Journal, had a piece last week (ironically) titled, “The Year Politicians Turned Their Backs on Economics.” There, Ip noted the Harris campaign’s various, if vague, proposals on rent control and price-gouging, and that “Trump has branded Harris’s proposals as socialism.” But, he continued, Trump “too has a soft spot for price controls. As candidate and president he routinely called for Medicare to negotiate drug prices.”

Negotiating drug prices is not a price control! Through Medicare, the federal government acts as a market participant, purchasing goods and services, including very expensive drugs. It could simply pay whatever price the drug company sets, or it could seek to negotiate a more favorable price. The latter, of course, is what we would expect any major purchaser of an expensive product to do.

Drug companies complain that the federal government through Medicare is the primary purchaser of their products, so it has too much power in the negotiation. As Ip puts it: “Given Medicare’s size, and the penalties for not cooperating, drug companies consider this tantamount to price controls.” Well, if the drug companies say so… But it’s hard to see how that is the government’s fault—drug companies are free to go find other buyers.

And here things get even more perplexing, because of course drug companies do have many other large markets for their products, in which they offer lower prices. As president, Trump’s argument was that Medicare should not pay more than other countries pay:

Until now, Americans have often been charged more than twice as much for the exact same drug as other medically advanced countries. … In case after case, our citizens pay massively higher prices than other nations pay for the same exact pill, from the same factory, effectively subsidizing socialism abroad with skyrocketing prices at home. … To address this unfairness and to lower prices for Americans, we’re finalizing the Most Favored Nation rule. … Medicare will now look at the price that other developed nations pay for their drugs. And instead of paying the highest price on that list — and we are substantially higher than any other country in the world — we will pay the lowest price.

So the federal government’s negotiating position is that it would like to pay a price that the drug company is already offering in other markets. Telling Americans, “well if you support that, you basically support price controls,” is a good way to make price controls appealing.

Addendum: Ip had actually noted just a few paragraphs earlier, “price controls are justified when a few companies enjoy market power, because they are monopolists or oligopolists, or because of an emergency. Those conditions don’t apply to apartments or food.” Hmm, do you know where a few companies enjoy market power? The sale of patented drugs. And do you know why they have that power? Because the government grants them the monopoly through patent law. So even if one did want to mock price controls on apartments and food while supporting them on drugs, the position would be an entirely consistent and economically coherent one.

IS LIFE A MICROECONOMICS TEXTBOOK OR NOT?

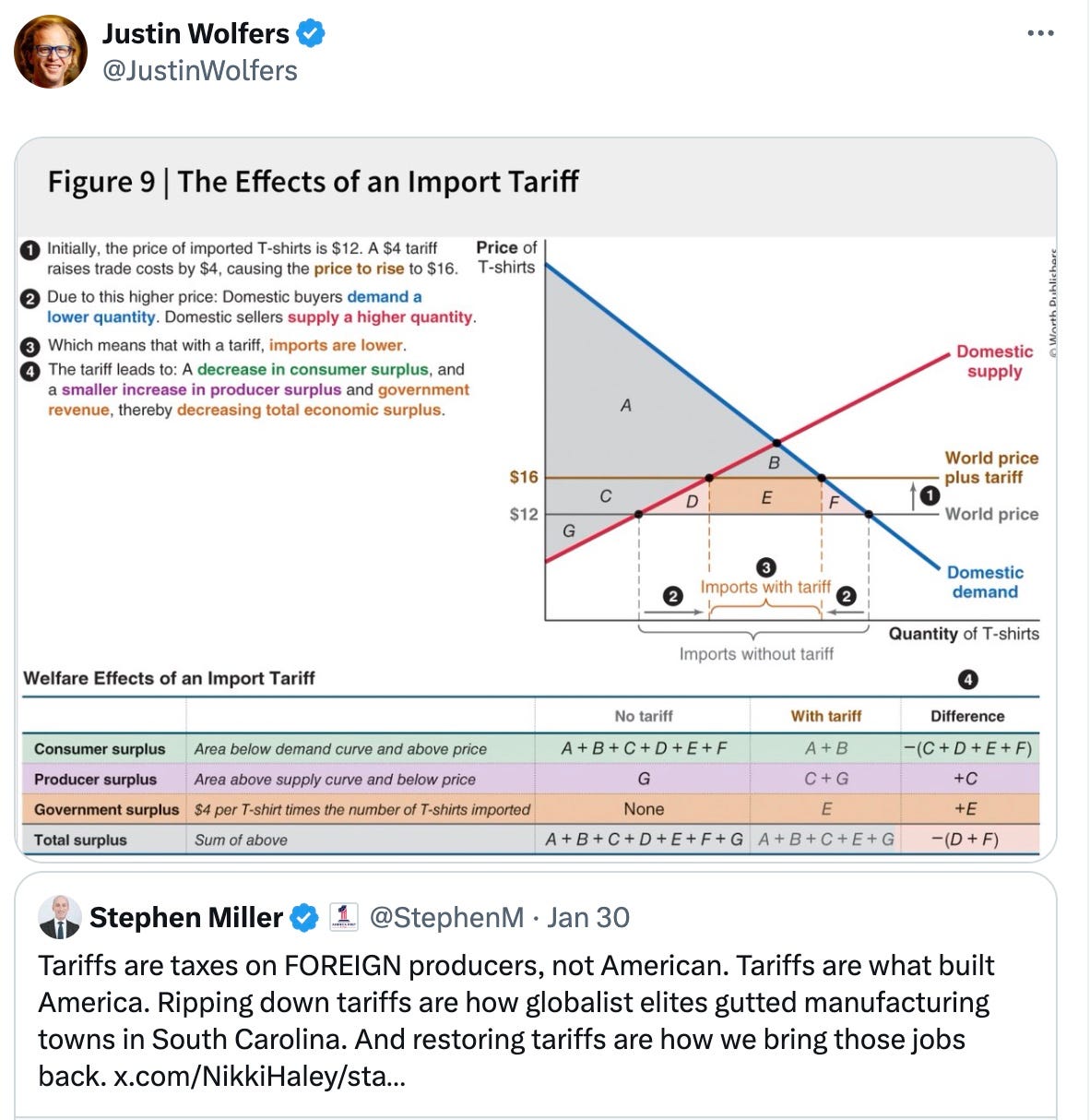

Some economists oscillate between condescendingly pounding the table for their Econ 101 model when it supports their preferences, and then thoughtfully contemplating the many nuances of sound public policy when Econ 101 no longer suits their purposes. University of Michigan professor Justin Wolfers especially excels here.

When the question is about Donald Trump’s tariff proposal, he has an Econ 101 chart ready to go:

But when the question is about Joe Biden’s rent control proposal, well: “Think of it as macro policy—setting a nominal anchor when the Fed's target isn't working—rather than as micro policy setting the relative price of housing.”

ONLY EXPERTS UNDERSTAND EXTERNALITIES…

Among the most foolish hobgoblins of the economic mind, the insatiable quest for the “externality” as justification for policy surely ranks high. Of course, externalities are real. Thinking about them can be helpful in identifying market failures and situations where policy is likely needed. But as a golden rule of policymaking—he who finds the externality gets to make the policy—it is doubly absurd: First, because externalities signal departures from what economists define as efficient market outcomes, but the efficient market outcome is not necessarily consonant with the common good or the appropriate objective for policymakers. Second, because the temptation quickly becomes overwhelming to work backward from whatever problem the economist wants to solve to the invention of an externality.

At The Atlantic, Brown University economist Emily Oster falls victim to this error—or else, commits an especially gruesome version of the crime, choose your metaphor. Asking “Should Parents Stay Home to Raise Kids?” she goes on at great length about how the evidence is mixed and there is no right answer, although everyone seems to think their own answer is best, and so “there is no ‘best’ choice.”

This would seem to be a strong endorsement of the emerging conservative model of family policy, which emphasizes providing equal financial support to all working families regardless of whether they use paid childcare or have a stay-at-home parent, over the progressive model, which emphasizes childcare subsidies that only benefit families in one arrangement.

But no, Oster seems also to think that her own family’s answer is best (“in my household, both parents work because it makes financial sense and because we want to”) and she has an argument for why that’s the approach public policy should support:

What the government can and should do is look for “externalities.” An externality occurs when the behavior of one person affects another, or society overall. The government may want to discourage a behavior resulting in a negative externality, and encourage a behavior resulting in a positive externality. You can make an externality-based argument for child-care subsidies. When people stay in the workforce after they have children, they pay more taxes.

The goal of family policy, in other words, should be to push parents away from the family arrangements they would prefer to choose, in an effort to generate more tax revenue. Thank you, economics! But don’t worry, Oster isn’t ready to write-off the stay-at-home parents entirely. “Parents who serve in the PTA, organize fundraisers, chaperone trips, and volunteer in the classroom have huge positive externalities. Paying them for this work would be an efficient and reasonable policy choice.”

You see, not only could we make our families more efficient by warehousing young children in commercial daycare facilities while their parents generate more tax revenue, but also we could make our civic associations more efficient by converting community efforts into paid work. Hiring people to run the bake sale is the “efficient and reasonable” choice. And then we could tax them on that income, and count it all as GDP growth, too.

HOW DOES EVERYONE KNOW THIS THING THAT ISN’T TRUE?

Finally, let’s give the media its due, for ineptly reporting on economic issues and then reporting the consensus reinforced by that ineptitude as itself a useful fact.

Interviewing Senator JD Vance on Meet the Press this weekend, NBC’s Kristen Welker pushed on the question of who pays the cost of tariffs. Trump’s tariffs, she said, “caused consumers to pay more, they paid more in taxes, $80 billion more.” Reporting on the exchange, Maggie Astor at the New York Times writes, “Mr. Vance denied that the tariffs Mr. Trump had imposed during his first term in office had raised prices for Americans, though data shows they did.” And “data shows they did” links to another Times story from 2020, “American Consumers, Not China, Are Paying for Trump’s Tariffs.”

They are all wrong, and specifically, they are wrong in assuming that any tariff paid is paid by consumers. Indeed, one discovers in the New York Times story, reading past the headline, that the tariffs were paid by “businesses and consumers,” “U.S. firms and consumers,” “voters and American businesses,” “consumers and importing businesses,” and “American importers.” Eventually, reference appears to a “study, published in October by researchers at Harvard University, the University of Chicago and the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston.”

That paper, “Tariff Pass-Through at the Border and at the Store: Evidence from US Trade Policy,” found that only about 5% of the cost of the tariff was actually being passed on to consumers. (The final version of the paper, published two years later, was more precise: “in response to a 10 percent tariff, the price of a typical affected import from China has only increased by about 0.35 percent relative to unaffected products in the same sector after 1 year.” And as the authors noted, “relatively little is known, however, about how economies in practice respond to tariffs, particularly when these trade policies involve large countries that have the potential to influence prices.”) Inflation data for the U.S. over the period when Trump’s tariffs were implemented likewise show no discernible impact on consumer prices.

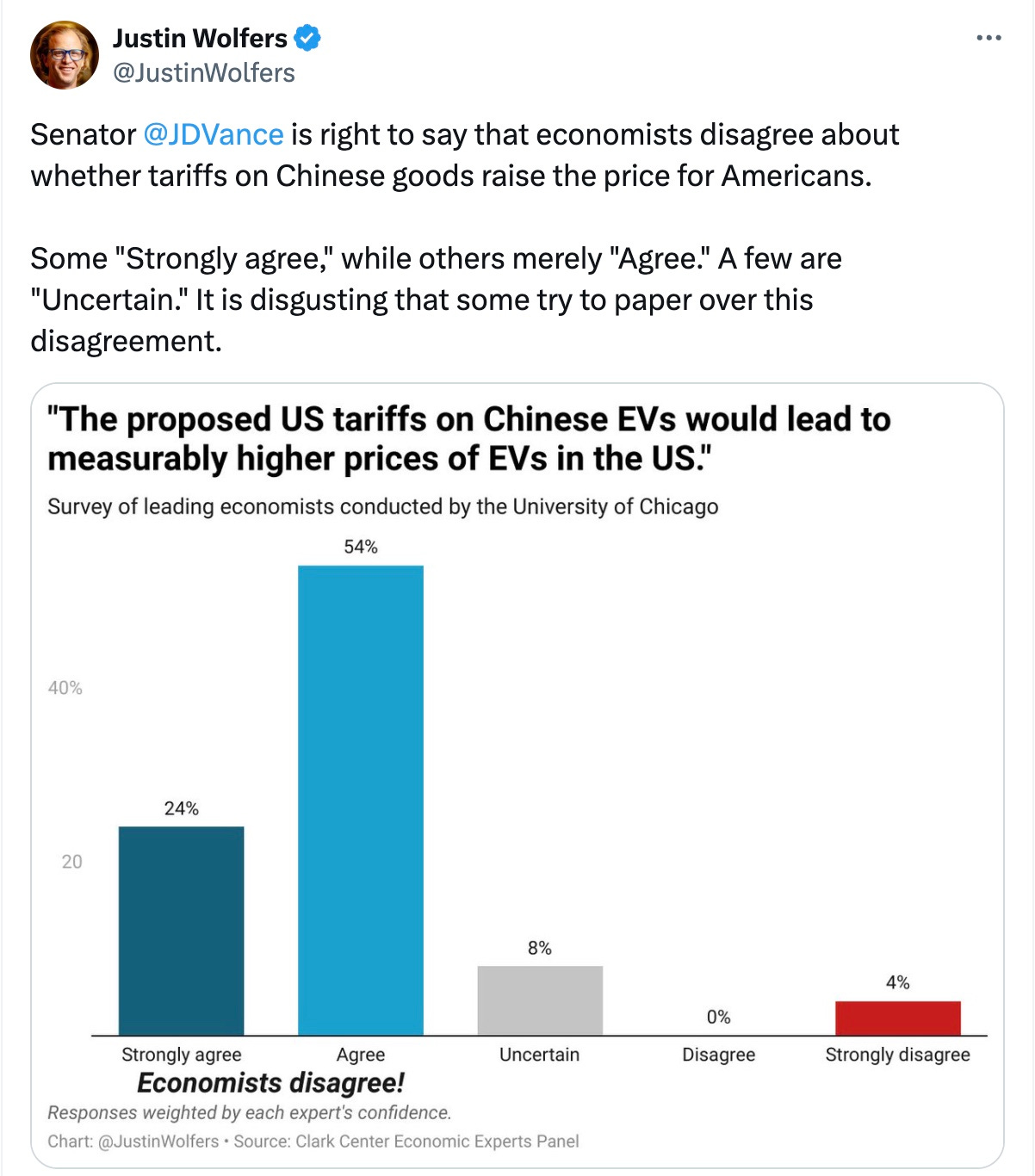

So when Welker said to Vance that Trump’s tariffs “caused consumers to pay more, they paid more in taxes, $80 billion more,” she was simply wrong. When the New York Times got confused by its own inaccurate headline and used it to support an attempted fact check, it was simply wrong. Coming full circle, Professor Wolfers was of course ready with a tweet:

His chart was for an entirely different tariff, much steeper and more targeted, imposed by President Joe Biden.

Helpfully, the University of Chicago survey of economists that Wolfers was citing has asked about the incidence of the Trump tariffs, and their economists overwhelmingly predicted “the incidence of the latest round of US import tariffs is likely to fall primarily on American households.” Of course, we know now that this was wrong, just like most things economists have been overwhelmingly predicting about trade has proved wrong. Will that temper the condescension in their next overwhelmingly agreed upon prediction? Ha!

BONUS LINK: One of my favorite things we’ve ever published at American Compass is this wonderful essay by Matthew Walther, “Marginal Prophets: The anthropology of magic explains economists better than economists explain the economy.”

Oren

So refreshing. Keep up the good work Oren

Exactly! Their track record over the last 40 years is dismal. So much proof now they are just mouth pieces for their handlers.

They all say and regurgitate the same blather because they go to their universities, and all talk the same blather to each other! lol

The university = The new religion

Great article, thanks. Hope your ideas rub off on the republicans. They need it, the no party has nothing to offer as they stand now.