I Finally Found the Perfect Economist Tweet

Everything wrong with the profession in just 280 characters

I finally found the perfect economist tweet. It is perfect in its economy of error, managing to get entirely wrong the theory, the analysis, and the data, all in three tight sentences—like “the quick brown fox jumped over the lazy dog,” but for bad public policy. It is perfect in its context, attempting to pile on to a colleague’s snide ridicule and instead landing at the bottom of the scrum. I may get it laser-etched in one of those little lucite paperweights, typically reserved for portraits of deceased pets and such, and keep it on my desk.

Marvelous.

Stevenson is a professor of public policy and economics at the University of Michigan and a member of the executive committee of the American Economic Association. She served with Furman on Obama’s CEA and as chief economist in Obama’s Department of Labor. She is co-author of a series of economics textbooks, and co-host of the “Think Like an Economist” podcast with fellow University of Michigan economics professor Justin Wolfers, who I wrote about in the aptly titled, “Against Justin Wolfers-ism.”

So this is pinnacle-of-mainstream stuff, not some obscure Marxist reddit thread. And whether you want to admit it, dear reader, you still have tucked in the back of your mind an intuition, drummed into you by your schooling and the media, that “well, they’re economists, I’m sure they must know what they’re talking about.” My solemnly sworn duty is to free you from that misconception and to persuade you that indeed economists often have no idea what they are talking about, that the dysfunctional culture of their profession compounds this problem with their absurd assertions, and that their abuse of the trust you have placed in them has helped lead the nation to its present challenges.

Of course, any great work of art must be situated within its context, which can be as important as the artifact itself. This all began when Jason Furman, former chair of President Obama’s Council of Economic Advisers, tweeted, “Short-run pain: Make consumers stop buying foreign toasters. Long-run suffering: Eventually America starts making toasters! But they’re more expensive & the jobs making them are worse than the ones they replaced. (Swap any manufactured import for ‘toaster’ & this still true.)”

Furman’s comment is obviously aimed at what he perceives as unwise policies being pursued by the Trump administration. He could have made many colorable points about the costs and benefits of the administration’s initial actions. He could have offered a thoughtful assessment of what his discipline’s actual research has to say about the longer-term efforts at rebalancing the global economy. But that would have meant being an economist, not a retweet-scoring pundit on social media, and Furman opted for the latter, which might be more fun, but which surely is not where his own comparative advantage lies.

“Make consumers stop buying foreign toasters,” is a bad start; no one is making consumers stop buying foreign toasters. “Eventually America starts making toasters! But they’re more expensive & the jobs making them are worse than the ones they replaced,” isn’t much better. The jobs may or may not be worse under various circumstances, but it doesn’t work as statement of some universal principle. And then he slathered on an unsupportable, absolute generalization for the sake of making his incorrect claim seem authoritative and scientific: “(Swap any manufactured import for ‘toaster’ & this still true.)”

Do academic economists have a standard contract provision requiring them to discredit their narrowly defensible points by making them as absolutist and implausible as possible?

I responded: “What is the theoretical or empirical support for the claim that, in the long-run, jobs making any currently imported goods will be worse than the jobs those workers would otherwise have? Or that, in the long-run, any otherwise imported good will be more expensive if manufactured domestically? Was that the result with Japanese cars? This seems like the sort of empty, absolutist rhetoric parading as economics that got us into this mess.”

This attracted the attention of Wolfers, who jumped in with a classic of the Wolfers oeuvre: “One thing some people do when they want to learn more about economic theory and empirical evidence is to study economics, perhaps at college, and often in graduate school. Some even spend their lives researching these questions. But tweeting is cool, too.”

Perhaps encouraged by her colleague’s brilliant riposte, Stevenson then dove in to demonstrate the limits of studying economics in college, perhaps in graduate school, even spending one’s life researching these questions. Apparently because tweeting is cool, too.

Stevenson has already deleted the tweet, which rather inadvertently makes Wolfers’s point, but the thinking behind it is still worth contemplating for a minute, as archetypal illustration of what economists get so wrong on so many levels. Let’s take each of the three sentences in turn.

1. The theory: “Theory says that we import what we have a comparative disadvantage in, which means precisely that the jobs are worse.”

Comparative advantage is not about job quality. Its premise is that trading partners can maximize their consumption by each allocating resources toward that which they can produce at relatively lower cost. Will that bear any correlation to the quality of the jobs involved in the production process? Maybe, maybe not. But it is a quintessential error of market fundamentalism to think that the pursuit of market efficiency will necessarily (or “precisely”) serve the goal of creating better jobs. (This is the basic premise of The Once and Future Worker.) The disconnect is doubly serious when foreign industrial policy and mercantilism, not some neutral force of market efficiency, is determining where production locates.

To make this concrete: Suppose, hypothetically, you had a country called Apan-Jay and a country called the Sunited Yates. The S.Y. can, at higher quality and lower cost, both (a) fabricate semiconductors, and (b) raise and slaughter cattle. A.J. is “better,” in absolute terms, at neither. But if it sinks enough subsidies into its chip sector it could get pretty good at chips; no matter what it does, it will never have enough open land to raise a lot of cattle. S.Y. would have a “comparative disadvantage” in chip-making and thus would import more chips and slaughter more cattle for export. Does this mean precisely that chip-making jobs are worse than slaughterhouse jobs?

Note also that, implicit in Stevenson’s model, we important what we have a comparative disadvantage in, and export what we have a comparative advantage in. She is suggesting (wrongly, but one can at least see the intuition), that we’ll have fewer jobs in things others can make well for us and more jobs in things we can make well for others. But if you release the assumption of the comparative advantage model in which goods and services are trade for goods and services, and instead allow deficits to accumulate, there’s no reason to believe that jobs lost to imports are replaced by jobs gained in exports. So the notion of comparative advantage is entirely beside the point. What you’d want to know is whether the production jobs are better or worse than the jobs in the non-tradeable service sector that in fact emerge to replace them.

Which brings us to…

2. The analysis: “Average hourly earnings in manufacturing are below US average hourly earnings.”

The economist’s habit of resorting to the broadest aggregate analysis is among the profession’s least attractive. The habit of switching at whim between static and dynamic analysis is among its most perfidious. This statement about two averages is not relevant to the question at issue, which was whether jobs in reshored American industry would be better than the alternative jobs those workers are likely to hold.

First, the averages might be useful, if the population of prospective manufacturing workers were a representative sample of the overall population. But of course, they are not. If one wanted to make substantive rather than performative points about the labor market’s structure, controlling for education would be a useful place to start. What are the average wages of the types of workers who have been harmed by deindustrialization and might return to a reshored manufacturing sector in that sector versus in others? One might also consider geography—what are the wage differentials in those places that have deindustrialized and are likely sites of reshoring? Somehow, in 2025, we have economists instead still doing the hand-waving that winners outnumber losers and can compensate them, so all’s good.

Fortunately, we also have economists doing good work on these issues, like David Autor and his colleagues, who have just released a paper on “Places Versus People: The Ins and Outs of Labor Market Adjustment to Globalization.” One way to think about whether the jobs that would come with reshoring are worse than the alternative would be to look at whether the alternative was better than the jobs lost to offshoring, for the people whose jobs were lost. The premise of Stevenson’s and Furman’s claims is that the answer is obviously yes. Autor finds the the answer is no:

“Most trade-induced job reductions in manufacturing reflect a loss of mid- and high-earnings jobs.”

“Jobs that comprise the eventual employment rebound in trade-exposed [areas] are disproportionately found at low earnings terciles.”

“To the degree that trade-exposed [areas] see net gains in high-premium employment, it occurs among college-educated workers only. Non-college employment falls in high-premium industries and rises in low-premium industries.”

Second, manufacturing wages today, after decades of deindustralization, are a poor proxy for what they might be in the long-run, with a renewed industrial base. As I have noted previously, we’ve damaged the sector so comprehensively that productivity has been falling there for more than a decade. Our deployment of robotics looks more like Slovenia’s or Slovakia’s than Germany’s or Japan’s. Our workforce development is in shambles. What would happen if we got those things right?

One place to look might be TSMC’s explosion of investment in Arizona. Per the New York Times: “nearby colleges and universities have ramped up their instruction in fields like electrical engineering. TSMC has collaborated with community colleges and universities through apprenticeships, internships, research projects and career fairs.” TSMC is funding student research projects. Clean rooms for training are being built, including one at a public high school system that offers vocational training. One community college offers an intensive two-week program that has graduated nearly 1,000 students:

“We have a generation of students whose parents have never once stepped foot into an advanced manufacturing factory,” said Scott Spurgeon, the [high school’s] superintendent. “Their concept of that is still much like the old mom-and-pop manufacturing where you show up every day and come out with dirty clothes and dirty hands.”

Precisely.

3. The data: “But jobs lost to trade are garment & agricultural, with wages even farther below.”

This is just untrue—an incorrect use of data to try and save an incorrect analysis in service of an incorrect theory. Have jobs been lost to trade in textiles and agriculture? In textiles, sure. In agriculture, maybe on balance, though the story is a lot more complicated and the U.S. was until recently a net exporter. Regardless, these are not the primary, let alone only, sources of decline.

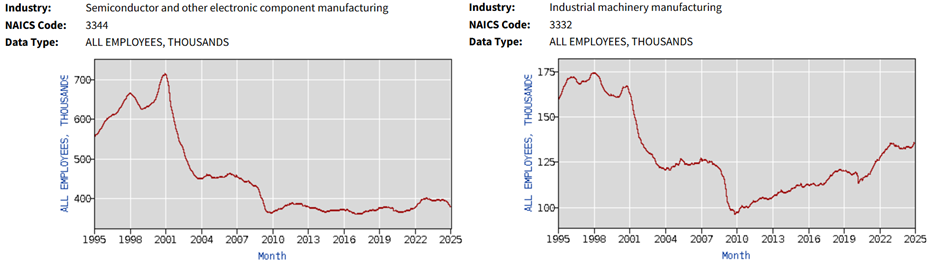

Here's the employment decline in semiconductors and industrial machinery, for instance:

Overall, from the Cold War’s end to 2024, the U.S. swung from a trade surplus to a deficit of $300B in advanced technology products.

People make mistakes in interpreting data all the time. But it’s hard to understand how anyone paying attention to trends in the U.S. economy and the effects of globalization over the past few decades could be under the impression that this is about t-shirts.

As you can probably tell, I find the sociology of all this at least as interesting as the economics. The whole exchange, from Furman to Wolfers to Stevenson, has the telltale signs of an academic field corrupted by overconfidence, insularity, ideology, a preference for attention and influence over critical thinking and rigor, and the social dynamics of a junior high school dance. That should sound familiar, because those are the same pathologies afflicting most of the other social sciences, giving rise to poor scholarship, radical politics, and the replication crisis.

Economists are different, the thinking went; they were more serious, less radical, heck this was practically a real science. Nope. And unfortunately, while most of those other disciplines speak mostly to themselves, accomplishing little besides wasting resources and immiserating graduate students, the economists claimed for themselves, and were granted, deference to shape our politics and markets. Oops.

So next time you discover a “consensus among economists” or read what “leading economists” have advised, just swap “economist” for “sociologist” and consider how the sentence would read. Of course, if they are good arguments, they are good arguments! Assess them on the merits. But that they come from an economist tells you little, besides buyer beware.

- Oren

Your style of argument against free trade reminds me of the knight on the bridge in Monty Python's Holy Grail movie. The discipline cuts off your arm, and you insist you're not hurt and you'll keep fighting. The discipline cuts off your other arm, and you say it's just a flueh wound. Trump smashes up the economy with numbskull tariffs, the stock market plunges because it makes America's economic future dimmer, and every decent economist can see perfectly clearly why this economic policy is destructive, but here you are flailing and somehow managing to miss the point.

You seem to think that standard free trade economics doesn't predict that the quality of the jobs under free trade will be better, only the living standard will be higher. But of course, people choose jobs based on job quality as well as earnings. When people have higher living standards, they're less willing to put up with miserable jobs. They demand better job amenities as well as nicer cars, niftier devices and more floor space. Employers competing for workers offer better job amenities along with everything else.

You seem to think it's evidence against the mainstream economics consensus in favor of free trade, that for many individual workers, the jobs they get under free trade aren't as good as those they would have had under protectionism. But economists always knew this perfectly well, and every mainstream economic textbook will emphasize that free trade has winners and losers. The traditional standard position is to advocate instituting free trade, and then compensating the losers, and trade adjustment assistance policies implement this advice.

I understand the need to lash out, since you've built a whole advocacy empire around not understanding basic international economics. Now Trump's idiot tariffs are providing a massive cautionary tale against your views, it does put you in an awkward position, doesn't it?

And there's also something admirable about the night on the bridge losing his limbs one by one, but none of his defiant courage. Admirable, but also pathetic.

Oren once again prefers debating with fellow elites and ignoring the authoritarian movement that continues apace. BTW, Gillian Tett, who Oren touted in his last piece, is on Ezra Klein’s podcast this week. Listening to her gives a much different take than Oren presented. Make sure to listen to the end, where she explains why Don terrifies her. Apparently Oren disagrees… Good luck America.