Note: I’m out Monday, so you’re getting something of an omnibus here to carry you all the way through the weekend and into next week. We’ve got the American Compass round-up, a very special Bankruptcy Court (Coercion Edition), and of course, what else you should be reading, but first…

In modern American politics, any movement, even a populist one, requires support from some group of elites and donors. A great challenge for conservatism in the past generation was that Wall Street supplied both. Not only the ethos, but also the self-interest of the hedge-fund manager steered the Republican Party’s message toward a hyper-individualism and market fundamentalism that was neither conservative, nor popular, nor wise.

Wall Street’s fading influence has been salutary, but in its place a community of influential entrepreneurs and investors from Silicon Valley, often called the “tech bros,” is ascending. Whether that aids construction of a durable, conservative governing majority depends on their priorities, how they understand their role, and how political leaders respond.

ONE THING TO READ THIS WEEK

Your one thing to read this week is “Trump Will Have to Choose: Populism or Elon Musk,” by Sohrab Ahmari at the New Statesman.

Ahmari focuses in on Donald Trump’s decision to participate with Elon Musk in a “Spaces” event on Musk’s X platform (formerly Twitter). A Spaces conversation with Musk, you’ll recall, is also the way that Florida governor Ron DeSantis chose to launch his own ill-fated presidential campaign. In each case, embarrassing technological glitches postponed the event. In each case, the event didn’t get much better once it did start, presenting the candidate in a bizarre light and focusing on niche issues. Trump ended up joking with Musk about the good fun of firing striking workers.

“By cheering Musk’s brutal treatment of his workers, the Trump campaign has sadly vindicated those who saw its pro-worker rhetoric as a mere façade,” writes Ahmari. And indeed, Musk’s track record on labor is awful. Of course, the same goes for Musk on China, seeing as he sold the U.S. down the river with his willing transformation of Tesla into a Chinese company. Musk is a loose cannon and a political liability, but he is considered cool within the niches of the typically young, way-too-online Right that seem bizarrely committed to repelling as much of the broad American middle as possible; a doppelgänger of the woke-Left campus activists determined to doom their own side even faster.

If conservatism merely swaps out the financial sector’s East Coast market fundamentalism for the tech sector’s West Coast techno-libertarianism as its driving force, the coalition will be no stronger. Every minute spent promoting cryptocurrency is a minute not spent talking to voters about things they care about or developing policies that might benefit the nation. Transgressively finding the most blunt and offensive way to phrase some logically defensible point may be good fun at the bar, but it is a disaster on the stump. Every time a politician touches this stove, he gets burned. The better metaphor is probably shoving a hand directly into a roaring fire.

To be clear, investors, entrepreneurs, and technologists should all be welcomed into the conservative coalition. Indeed, given their economic outlook and cultural commitments, and given the alternative of current progressivism, they obviously belong on the Right side of the aisle. But they also have to understand that being good at building companies is not the same as being good at politics, and indeed that the more they confuse the two the more they will be undermining their own goals. Politicians, likewise, need to remember that their job is not to score invites from the people they want to get a beer with, it is to be that person for the typical voter.

BONUS LINK: At the start of the pandemic, venture capitalist Marc Andreessen wrote a powerful manifesto, “It’s Time to Build.” This is an excellent example of how the tech community can engage constructively, drawing on its areas of genuine expertise to amplify an aspirational and broadly appealing message.

THIS WEEK AT AMERICAN COMPASS

The Compass Point is from the Ethics & Public Policy Center’s Patrick T. Brown, on the structure of childcare policy today and the confused cases often made for its reform: Building Blocks for Childcare Reform.

Across America, families are making childcare work—without the billions of dollars of subsidies envisioned by progressive advocates. Three-quarters of parents tell federal surveys they have good choices in their choice of childcare. And about 40% of families with young kids don’t have any kind of regular childcare arrangement, preferring a stay-at-home parent or balancing care between parents and relatives.

For families that rely on paid childcare, policymakers can doubtless do a better job of expanding the choices available to them. But understanding the correct policy approach starts with understanding the problem, and what current policy approaches get right or wrong. Bipartisan proposals to subsidize demand by expanding tax credits for childcare approach the problem backward.

Also on The Commons:

Democrats’ Disdain for Democracy: American Compass managing editor Drew Holden questions the plan to save democracy by intentionally obscuring a candidate from the voters.

Can “Kamalamania” Continue to Election Day? EPPC’s Henry Olsen draws lessons from the similar but short-lived burst of joy that propelled former New Zealand prime minister Jacinda Ardern.

And, on the American Compass Podcast this week, University of Winchester professor and economist Richard Werner joins me for a wide-ranging but accessible primer on the foundational debates raging about money and banking.

We interrupt your regularly scheduled Friday readings for… a special BANKRUPTCY COURT: COERCION EDITION

The inability of the libertarian mind to grapple with the gray areas of real life is a recurring theme here at Understanding America. I recently commented in an interview that: “It's advantageous for Libertarians that their ideology is so simplistic it fits on a bumper sticker. Reality is complicated.”

This generated a pitch-perfect reply from Reason Magazine’s Nick Gillespie, “Reality *is* complicated, which is why government shouldn't be.” What does that even mean? Because reality is complicated, we should think it wise or plausible that the institutions governing it be simple? Yes, that is what libertarians think. But one can see how it might obstruct having useful thoughts on politics, economics, or public policy.

An excellent example comes this week from Richard Hanania, who is appalled by the “coercion” of organized labor. Labor law not only creates situations where one must be represented by a union as a condition of employment, he laments, but also leaves employers no choice but to bargain in good faith. As Monty Python’s Constitutional Peasant might say: “Help, help, I’m being repressed.”

Look, the presence of a compulsory labor organization obviously brings with it tradeoffs, which should not be ignored. But let’s not pretend that being forced to accept some condition of employment is some unprecedented imposition on workers. Employers impose lots of conditions of employment. In The Wealth of Nations, Adam Smith warned that workers face coercion in the absence of collective action. “Upon all ordinary occasions [employers] have the advantage in the dispute, and force [workmen] into a compliance with their terms.” Force into compliance.

The employer “forced” to negotiate with a collection of its workers is less “free” than the hunter-gatherer wandering unfettered through the forest. But also, it’s (typically)… a corporation—a creature of the state chartered in the public interest. Hanania is upset that unions enjoy “immunity from broadly applicable laws.” So do corporations. Nor is the alternative to labor’s coercion the freedom that a hunter-gatherer once enjoyed to run his aerospace manufacturer however he damn well pleased. Rather, the workplace will be governed by (coercive) employment law but also enjoy the benefit of connection to roads and water pipes constructed with proceeds from the government’s (coercive) collection of taxes.

Indeed, what’s so funny about the title of the piece, “Organized Labor Requires Government Coercion,” is it’s sheer banality. The same applies to pretty much any institution in a modern society. Law and order. Public services. Functioning markets. In all cases, the question for policymakers is the tradeoff: How much coercion, by whom, to what end? That libertarians do not know how to ask, let alone answer, such questions is rather a large problem for their project.

WHAT ELSE SHOULD YOU BE READING

Re: Loose Labor Markets Sink Ships… Bloomberg reports on how Cheap Foreign Labor Soars in Canada as Young Workers Are Left Jobless.

This is very good reporting on the damage temporary worker programs are doing to the Canadian labor market:

Entry-level jobs for students and recent graduates are much harder to find as the economy weakens, yet the country has also imported hundreds of thousands of temporary foreign workers for jobs, many of them in the food and retail sectors. That’s contributing to a soaring rate of youth unemployment. … For younger immigrants — those who’ve landed in Canada in the past five years — the unemployment rate is around 23%.

And, yes: “The use of the program may not only be making it harder for youths to get jobs but also suppressing wages for the entry-level positions where they compete with foreign workers.”

Re: Elite Failure and Repeat Games… Yuval Levin writes on The Trust Trap.

Levin is the foremost contemporary analyst of American institutions, and here he dives into the question near and dear to my own heart of how elite institutions in particular have been failing so miserably. Most commentary emphasizes on the simple reality that they’re doing a bad job, but that strikes me as inadequate and also somewhat question-begging. Why are they doing a bad job? Levin’s answer: “Greater public faith in elite institutions requires evidence of restraint, not just of competence.”

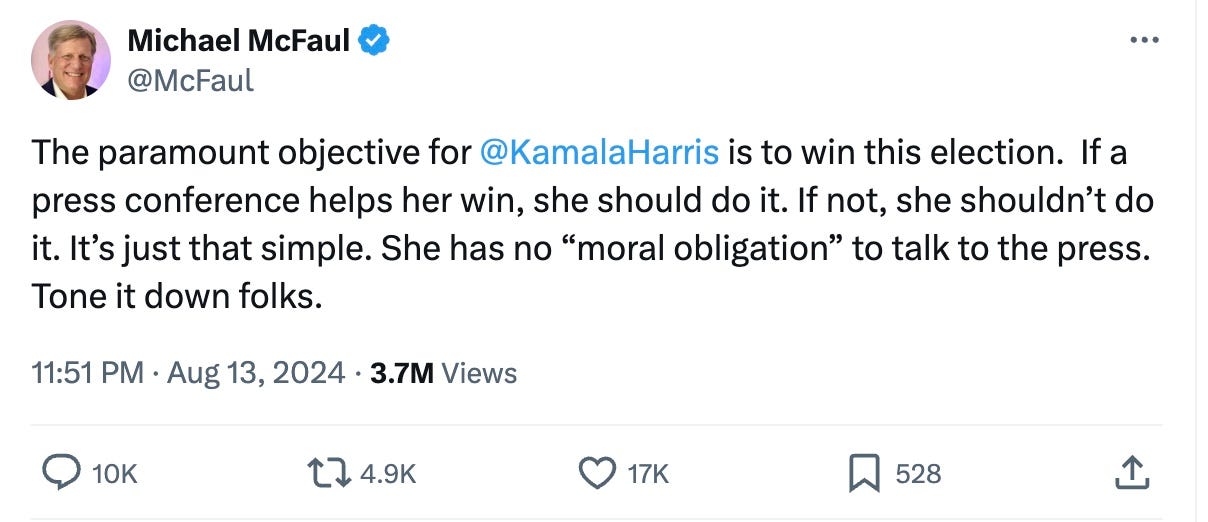

I found this especially helpful in clarifying something I’ve been thinking a lot about, which is the perplexing failure to recognize that public leadership is a repeat game. Leaders on each side behave constantly in ways that they know would outrage them if coming from the other side. No one cares about hypocrisy because the immediate end always justifies the means. A favorite example from the other day comes courtesy of Michael McFaul, who served as U.S. Ambassador to Russia in the Obama administration and is now a professor at Stanford University and a senior fellow at the Hoover Institution:

McFaul clearly thinks it’s OK to say this now, because it furthers his objective of supporting Kamala Harris, and at some point will be OK as well to revert to his once and undoubtedly future position that political candidates in a democracy do indeed have an obligation to talk to the press. He assumes this has no consequences, because he will not be held accountable.

But the consequence, as Levin makes clear in his excellent essay, is to the social framework in which elites have any credibility at all. “In effect, the public’s mistrust of elites has more to do with character than competence — and with a sense that the ambitions of the leaders of important institutions aren’t being harnessed in the service of others,” he writes. “Trust in experts and elites is the result of some perception of this kind of formative restraint even more than of a recognition of their ability or competence.”

Exercising restraint never seems desirable in the moment (that’s what makes it restraint!), but it is precisely that exercise which qualifies someone as more than nakedly self-interested in the eyes of the public. Read the whole thing.

Re: Tech-Broship Done Right… Tablet profiles Anduril’s Palmer Luckey in American Vulcan.

Notwithstanding the Elon Musk problem described above, great inventors and entrepreneurs have important and socially invaluable talents. It’s just that policy analysis and political leadership are not necessarily among them. This profile of Palmer Luckey, inventor of the Oculus VR headset and now founder and leader of the foremost innovator in defense technology, underscores the upside of the disruptor. The question for our nation is how do we create as much space as possible for our Musks and Luckeys to do great things in the realms where their talents merit and reward that space without granting carte blanche to wreak havoc in other realms where their instincts and habits are unhelpful or even destructive?

Re: The Domestic Economics of Free Trade… On Bloomberg TV, AEI’s Michael Strain gets asked to “make the case for free trade. What do we expect? What do we get out of that?” The answer is fascinating (full clip here):

So a lot of politicians talk about trade as a jobs program, and I think that's the wrong way to think about trade. What trade is really about is consumption. What trade is really about is productivity. What trade is really about [is] higher wages for workers, higher incomes for households over the long term.

That's why you want to trade. You want to trade because trade allows each nation to specialize in that nation's comparative advantage. That makes the workers in that nation more productive, that makes them more valuable to businesses, that makes businesses compete more aggressively for them. The way businesses compete more aggressively is by bidding up wages. So now you've got higher wages, higher incomes, and higher living standards. That's the way we should be selling trade. In terms of the level of employment, that's really a job for the Fed. …

Trade is not about how many people are working, trade is about what are workers doing. And if you allow free trade, what you're going to get is a situation where what workers are doing is what they are best at, what they are most productive doing, and that's how you get higher wages and higher living standards.

I love this answer so much: A brief mention of consumption and then total capitulation to the framing that trade must be held accountable for its effects on the labor market and the quality of jobs. This matters. It matters because it concedes that making things matters. And as a result, it concedes that if free trade is yielding huge trade deficits, it is not working, and the case for it is not there.

In the consumption-obsessed framing of the Old Right’s market fundamentalism, free trade’s primary selling point is that it lowers prices and increases choices for consumers. Imports are the point, the more the better, and exports are just the price the country has to pay for its imports. In that case, trade deficits are irrelevant, or even good. If we can get even more imports, and not even have to pay for them in production of our own—instead sending out assets like debt, equity, and real estate—all the better.

But in Strain’s framing, that won’t fly. The reason you want trade is that trade “makes the workers in that nation more productive, that makes them more valuable to businesses, that makes businesses compete more aggressively for them.” Yes, that sounds great! But if goods once made in America are instead made abroad and imported, and no commensurate opportunity emerges for Americans to instead make something else that they can send in return (“trade,” if you will), then none of that happens.

“If you allow free trade,” says Strain, “what you're going to get is a situation where what workers are doing is what they are best at, what they are most productive doing.” That may be true if trade is balanced. But if you simply lose the manufacturing jobs and send workers scrambling into a deficit-financed services industry where their productivity may well be lower, you can’t tell this story.

The case Strain is making is not for “free trade,” but for “free and balanced trade.” Hear, hear. And if free trade is not balanced trade, policymakers will have to act.

Enjoy the weekend, and the week too! Back with more next Friday.

“The coverup of President Joe Biden’s cognitive decline and the resulting coronation, absent a primary vote, of Vice President Kamala Harris should make one thing clear to would-be Democratic voters: the party views you with disdain.”

100% swinging RIGHT

Free trade, assuming such a thing exists, is efficient. However, it is dangerous as the last few years have proved. Indeed, the slow infusion of poison into Middle America over the last 4 decades is dangerous too, just slower acting and less obvious. Autarchy is less efficient but safer and the US is probably better placed than anyone to do this. If you want an example, consider Russia (second in the autarchy ranking) when faced with an unprecedented assault on trade and financial arrangements is doing just fine economically. Complete implementation is impossible and trade will be required but it should be so structured to be in our national interest.