Against Justin Wolfers-ism

The temptation to use economics as propaganda does not serve economists well

Is economics really simple or really complicated? As with most questions in the field, the answer seems to be, “it depends.” For too many economists, though, it depends in particular on their own politics.

The case against tariffs can be conveyed easily with a supply-and-demand chart. But don’t use that same model to show how high levels of immigration might put downward pressure on wages… such a simplistic framework can’t possibly convey the complex interactions of a modern economy. Anyone who has taken Econ 101 can make the case for a carbon tax as the efficient correction for a negative externality. But making the Econ 101 case against a minimum wage increase will get you laughed out of the room. Incredibly, the dismal science proves every time to be precisely as unyielding or as pliable as necessary to support the policy agenda of the Democratic Party and, perhaps more importantly, the sensibilities of a Davos Cocktail Party.

Justin Wolfers, a professor at the University of Michigan, personifies this dismal approach to the dismal science. I should say, I have never met Professor Wolfers and have no personal animus toward him. For all I know, he’s a great guy and a great teacher. But as a prominent public commentator and online personality, a teacher of Economics 101 at one of America’s largest universities, and the author of a widely used introductory textbook, he is the sort of economist whose approach matters in the public square and bears scrutiny. And that approach illustrates well what has gone wrong in economic policy debates.

The problem with trying to conduct economics unmoored from coherent principles is that it quickly falls apart, necessitating further departure from principle, leading to further crumbling. Wolfers has provided a good example over the past few weeks with his effort to make the case against tariffs through a case study of the Trump administration’s 20% tariff on washing machines, imposed in 2018. A 2020 analysis in the American Economic Review found that prices for washers and dryers both increased by 12%. Because consumers typically buy the units together, sellers spread the price increase across both and in fact the total price increase appeared to exceed 100% of the tariff impact.

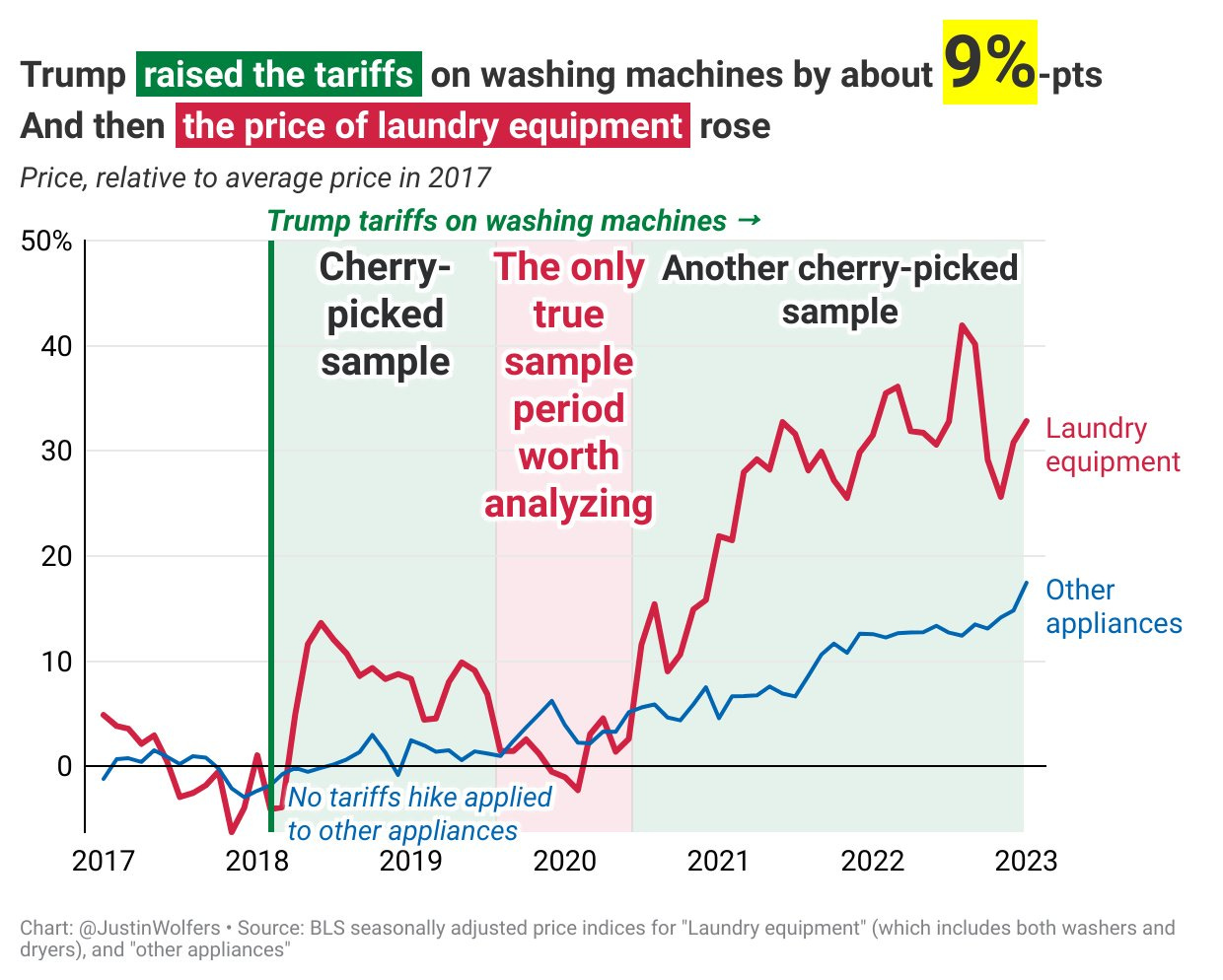

“The 2018 tariff hike on washing machines was an impressively destructive policy,” Wolfers concluded. Helpfully seeking to communicate the finding to the public, he posted a simplified chart on X, comparing laundry equipment prices to other appliance prices, captioned: “Trump raised the tariff on washing machines by about 9%-pts and the price of laundry equipment rose by about 9%.”

But the AER analysis considered prices only four and eight months after the tariffs took effect, and Wolfers cut off his own chart a few months later. Extend the data out to the end of 2019 (prior to the onset of COVID), and the effect vanishes.

This is embarrassing, obviously—but hey, everyone makes mistakes. And besides, the broader view does not negate the earlier point (that in the short-run, tariffs at least seemed closely correlated with price increases). Rather, the broader view complicates the picture, as an economist interested in economics might even be eager to highlight. Here is a classic illustration of a tradeoff, between a short-run price impact and a longer-run gain in domestic production with prices returning to prior levels.

But under Wolfers-ism, complexity is unwelcome, except when needed of course. Looking at the upward pressure that high levels of immigration place on housing, Wolfers has wildly inapt charts rejecting the existence of a border crisis and misleading interpretations of elaborate models. President Biden’s rent control proposal is serious and sophisticated, he says. But washing machine tariffs cannot be accorded such courtesy.

So instead, Wolfers doubled down. When someone observed that tariffs will have different effects in different situations, he responded, “I don't really think the laws of supply and demand care about your intentions, although I agree that it would be nice if they did.” And then he made a new chart showing price trends all the way through 2023.

The chart mocks the idea of focusing on just the period in late 2019 and early 2020 when washing machine prices had fallen back below other appliance prices. In an accompanying tweet, Wolfers described a focus on that period as an attempt to “zoom in and focus only on what's happening during a global pandemic.”

Now there were two problems. The first was that the “global pandemic” claim was simply false, and Wolfers knew it was false because he had constructed the data set himself. The highlighted portion of the chart, where washing machine prices had fallen, stretched from summer of 2019 to spring of 2020—that is, before, not during, the global pandemic. What his chart showed was prices normalizing and then, when prices went haywire with the pandemic’s onset, they went haywire in the appliance market too.

But more importantly, this new chart did nothing to substantiate his original effort to link the tariff with the price increase. To the extent that a constant tariff affects a consumer price, it should do so as a one-time change in the price level. It does not put continual upward pressure on the price. The decline in washing machine prices (relative to other appliance prices) in 2019 is inconsistent with the tariff continuing to pass through to consumer prices. The surge in washing machine prices during the pandemic only goes to further underscore that trends in washing machine prices do not necessarily have much to do with tariff levels.

What’s remarkable is the number of experts who circulated the chart as somehow useful—the Manhattan Institute’s Brian Riedl, recent Council of Economic Advisers chief economist Ernie Tedeschi, Cato’s Scott Lincicome, AEI’s Norman Ornstein… It would be insulting to suggest they did so after critically evaluating its premise; far kinder is an assumption that blind tribal allegiance fueled too-quick slamming of the “Retweet” button.

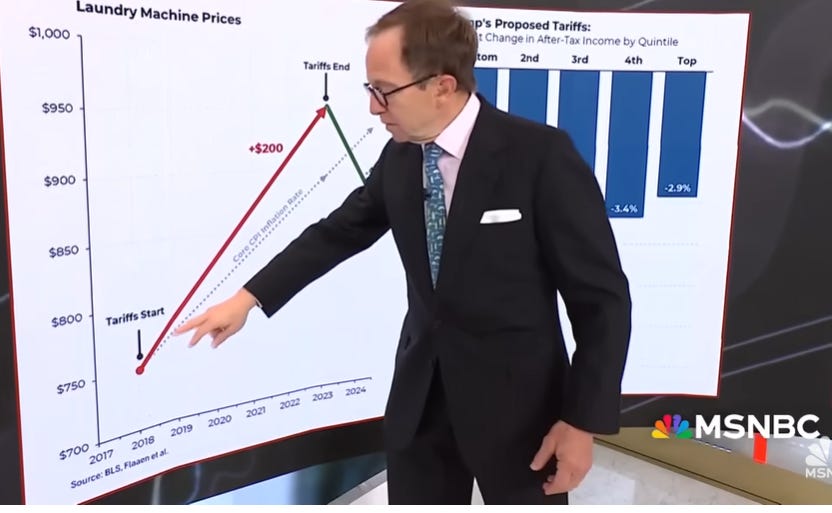

But special mention goes to Steven Rattner, former head of the Obama Auto Task Force and now Morning Joe Economic Analyst. “What are the facts?” Joe Scarborough asked Rattner on MSNBC. Speaking “as an economics guy,” Rattner explained his chart.

“These are laundry machine prices. Trump imposed tariffs on them back in 2018. Prices immediately, or over a period of time, went up over 200 dollars.”

This is where Wolfers-ism ends up: bad analysis in service to ideology gets laundered (pun intended) into a chart dumbed down to the point of incoherence and outright falsehood. Now we see laundry machine prices increasing steadily over time, in response to a tariff imposed at a point in time? To obscure the fact that the tariff’s actual effect on prices was short-lived? To quote Billy Madison’s Principal Downey, “Everyone in this room is now dumber for having listened to it. I award you no points, and may God have mercy on your soul.”

In “Free Trade’s Origin Myth” (one of my favorite essays, go read it if you haven’t!), I quote Alfred Marshall, often considered the father of modern economics, from his seminal 1890 textbook. Writing about Friedrich List, a political economist who advocated industrial policy and tariffs, Marshall observed, “Many of [List’s] arguments were invalid, but some of them were not; and as the English economists scornfully refused them a patient discussion, able and public-spirited men impressed by the force of those which were sound, acquiesced in the use for purposes of popular agitation of other arguments which were unscientific, but which appealed with greater force to the working classes.” This should sound familiar.

I will conclude here as I did then:

The economists’ mistake is one prevalent in many fields today, from public health to education, where attempts to launder genuine expertise into social control tend inevitably to backfire, discredit the experts broadly, and thus fuel precisely the populism that they seek to avoid. Telling Americans to believe “economics” over their own lyin’ eyes only underscores how economics has failed. Heaping scorn on departures from the free-trade orthodoxy probably succeeds in cowing people who care mostly about their own respectability, but the inevitable result will be to sideline the economists themselves from the policy debates to come.

That would be a shame. As the American people, and American policymakers, rediscover the importance of promoting domestic industry and protecting the domestic market, economists have a vital role to play in analyzing how best to accomplish the nation’s goals. What should replace the WTO and how could it facilitate the genuine free trade that Smith, Ricardo, and Mill encouraged while foreclosing the dysfunctional perversions that have emerged? What drives the US trade deficit and what could reduce it? What forms of industrial policy most effectively channel investment toward vital industries while minimizing waste and abuse? Which industries are most vital? If economists would leave the political dreams to the politicians, they could do much good addressing questions like these. That is, after all, their comparative advantage.

Oren

The poster child for this is Krugman. I have wondered how on earth did this guy get a Nobel Prize. When I went back and read some of his stuff from the 1990s it did make sense in the context of the times. He went completely insane after the 2000 election. To be broken by W, is really embarrassing.

Well done Oren. Unfortunately, too often "economics" is simply "politics" dressed up in fancy clothes. Too often, economics is "bullshit baffles brains", as my friend used to say, intended to overwhelm the audience.